The allure of distilled spirits—clear, potent, and sometimes intoxicatingly complex—has fascinated humanity for centuries. Among these, grain spirits hold a special place. From the humble beginnings of home distillation to the refined artistry of craft distilleries, the process of turning grains into a clean, smooth, and flavorful spirit is as much science as it is an art. But is there truly a “secret art” to distilling grain spirits, or is it simply a matter of following chemistry and tradition? Let’s dive in, step by step, and uncover the subtleties, expertise, and craft behind the world of grain spirits.

The Foundations: Understanding Grain Spirits

Before exploring any secret artistry, it’s crucial to define what grain spirits are. Grain spirits are distilled beverages produced from fermentable grains such as corn, wheat, barley, or rye. Unlike wine or cider, which derive their sugars from fruits, grain spirits rely on starches that must first be converted to sugars through malting or enzymatic treatment. This process is called saccharification, and it’s the first crucial step where skill starts to shape the final product.

For example:

- Corn: High in starch, typically yields sweet, smooth spirits (think bourbon).

- Rye: Produces a spicier, more robust flavor profile.

- Barley: Often used in whisky, contributes malty, nutty notes.

- Wheat: Lends a softer, sweeter, and sometimes creamier mouthfeel.

While any grain can technically be distilled, each brings a unique personality to the spirit, and the choice of grain already signals part of the master distiller’s intent.

The Alchemy of Fermentation

If the grains are the raw canvas, fermentation is the painter’s brush. This is where sugars are converted into alcohol and countless flavor compounds, under the careful guidance of yeast. But here is where artistry truly begins to peek through. While anyone can throw yeast at a sugar solution, a skilled distiller understands that yeast selection, fermentation temperature, and time are critical levers for shaping character.

- Yeast Strains: Different strains of yeast produce varying levels of esters, phenols, and fusel alcohols. Some may bring fruity notes reminiscent of pear or banana, while others impart spicy or floral undertones.

- Temperature Control: Warmer fermentations tend to increase ester production, creating complex, fruit-forward notes. Cooler fermentations can yield cleaner, more neutral spirits.

- Fermentation Time: Too short, and the sugar isn’t fully converted. Too long, and unwanted compounds accumulate, leading to harshness. The master distiller watches and tastes constantly, adjusting as needed—a subtle skill that balances science and intuition.

In essence, fermentation transforms simple starches into a dynamic, living solution, ready to be distilled—a step that is part laboratory, part intuition.

Distillation: Where Science Meets Magic

Distillation is the stage most often associated with secret knowledge. The principle is simple: heat a fermented mash until alcohol vaporizes, then condense it back into liquid. Yet within this simplicity lies infinite nuance.

Types of Stills

- Pot Stills: Traditional and artisanal, pot stills excel at producing spirits with rich, complex flavors. Each distillation is a slow, careful process, often repeated multiple times.

- Column Stills: Modern and efficient, column stills can produce higher-purity spirits at scale. They are less forgiving, requiring precise control to avoid stripping away desirable flavors.

- Hybrid Stills: Some distillers combine pot and column elements, seeking a balance between flavor complexity and efficiency.

Cuts: The Heart of the Spirit

Even the best distillation equipment can’t create a great spirit without careful cuts. Distillers separate the distillate into three fractions:

- Foreshots: The first vapors, often containing methanol and other volatile compounds, are discarded.

- Heart: The core of the distillate, this is the prime drinking spirit.

- Tails: Heavier, oilier compounds that, if included in excess, can make the spirit harsh. Some distillers recycle part of the tails into the next batch to retain character.

Here lies the subtle artistry: deciding when to cut from foreshots to heart and from heart to tails is often as much about smell, taste, and instinct as it is about numbers. The best distillers describe it as listening to the spirit, as if it has a voice telling them when to act.

Water and Its Role

One often overlooked element is water quality. Water makes up a large portion of the final spirit after dilution. Its mineral composition can subtly alter mouthfeel, perception of sweetness, and even how flavors unfold. Soft water may yield a smooth, silky finish, while harder water could add structure and a slight minerality. Distillers sometimes go to extraordinary lengths, filtering, blending, or sourcing specific water for a particular spirit—a reminder that grain spirits are not only about grains.

Maturation: Time, Wood, and Patience

Many grain spirits are bottled immediately, like vodka, while others benefit from aging. The aging process, typically in oak barrels, is another layer of artistry.

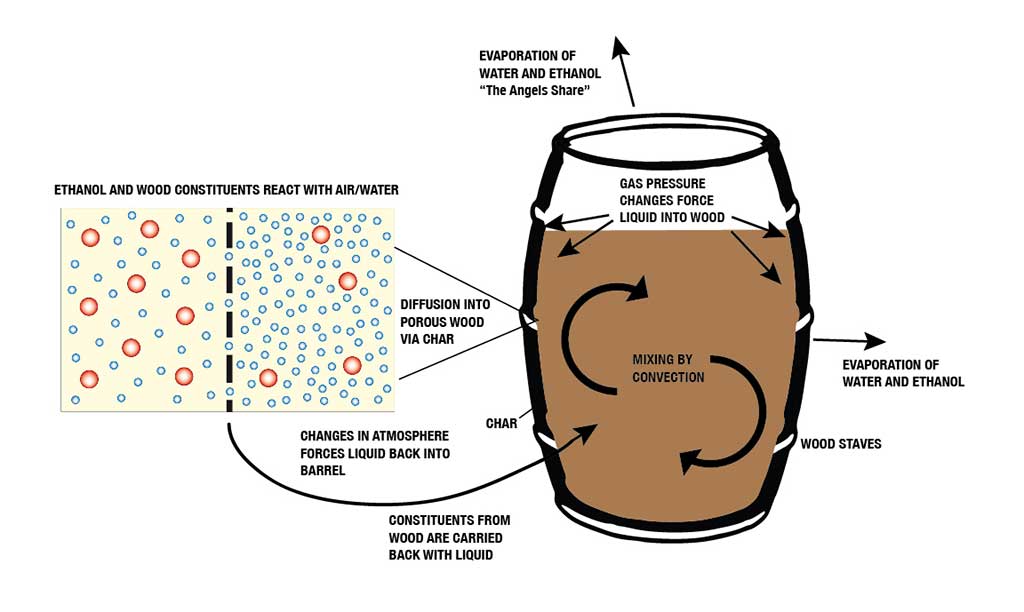

- Wood Selection: Different species of oak impart different flavor compounds, from vanilla to smoke to tannin.

- Toasting and Charring: Inside a barrel, the wood is often toasted or charred. This triggers chemical reactions that create caramelized sugars and phenolic compounds.

- Barrel Size and Age: Smaller barrels accelerate extraction; older barrels contribute subtler nuances.

During aging, the spirit undergoes complex interactions with oxygen, wood, and residual compounds, gradually developing richness and depth. Here, patience is an art in itself, as the timing of bottling can make or break the expression.

Flavor Nuance: The Invisible Touch

Even after distillation and maturation, a spirit’s final character depends on nuanced adjustments. These can include:

- Dilution to Bottling Strength: Lowering the alcohol to 40–50% ABV is common, but the choice affects body, aroma, and mouthfeel.

- Blending: Some distillers blend multiple batches or ages to achieve a consistent profile, creating harmony between diverse flavor notes.

- Filtration: Charcoal filtration or other methods may be used to remove harsh elements without stripping character.

In each step, the decisions are subtle, informed by experience and taste rather than strict rules. This is where the “secret art” truly resides—a combination of knowledge, intuition, and personal style.

Regional Identity and Cultural Influence

Grain spirits also carry cultural fingerprints. For instance:

- American Bourbon: Dominated by corn, often sweet and full-bodied, matured in heavily charred new oak barrels.

- Canadian Rye: Typically lighter, smoother, with a subtle spice, often blended.

- Russian Vodka: Generally distilled multiple times for neutrality, emphasizing purity.

- Japanese Whisky: Inspired by Scotch traditions, yet often lighter, precise, and subtly nuanced.

Understanding and preserving regional characteristics is part of the artistry. It’s not just about chemical composition—it’s about storytelling, heritage, and identity.

Misconceptions About “Secrets”

There is a romantic notion that the finest spirits are made through secret recipes, hidden techniques, or mystical rituals. In truth, most of what makes a spirit exceptional can be explained scientifically. What separates great distillers from good ones is less about guarding secrets and more about experience, sensitivity, and decision-making under uncertainty. They know when to bend rules, when to intervene, and when to let nature take its course.

Technology vs. Tradition

Modern distillation benefits from precision tools: temperature sensors, automated stills, and chemical analysis. Yet the human element remains indispensable. A purely automated process risks producing a spirit that is technically flawless but lacking in soul. Great distillers use technology as a canvas enhancer rather than a replacement for artistry.

Tasting the Art

Ultimately, the proof is in the glass. When tasting grain spirits, the nuances are subtle:

- Nose: Fragrance, from sweet grains to floral esters, hints at fermentation and distillation choices.

- Palate: Texture, balance of sweetness, spiciness, or creaminess, showing the influence of grain, cuts, and water.

- Finish: The lingering sensation and how flavors evolve, influenced by aging and blending.

The careful observation of these layers reveals the fingerprint of the distiller, akin to recognizing a painter by their brushstrokes.

Why Grain Spirits Inspire Obsession

For enthusiasts and professionals alike, the fascination with grain spirits lies in their complexity. Unlike wine, where terroir often dominates, or beer, where hops and yeast shine, grain spirits represent a delicate interplay:

- Raw material selection

- Saccharification

- Fermentation

- Distillation cuts

- Water and dilution

- Aging and wood interactions

- Final blending and bottling

Every step is both a science and an art. Each bottle tells a story, shaped by choices that are invisible yet profoundly felt in taste and aroma.

Conclusion: The Secret Is in the Mastery

So, is there a secret art to distilling grain spirits? Yes—but it’s not hidden in recipes or rituals. The secret resides in mastery: understanding grains, yeast, fermentation, distillation, water, and wood; making hundreds of subtle decisions; listening to the spirit at every stage; and having the patience to wait for perfection. It’s an intimate dance between science, craft, and intuition—a craft honed over years, often passed from one generation of distillers to the next.

Grain spirits may appear simple in a glass, but each sip is a testament to human ingenuity, meticulous attention, and an almost poetic interplay of natural forces. The true secret isn’t locked away—it’s experienced, felt, and tasted.