When we think of terroir, our minds usually drift to sun-baked vineyards, mineral-rich soils, and the gentle slope of hillsides. Terroir is that elusive essence that gives wine, and other fermented products, their identity. Traditionally, soil, climate, and geography have been considered the holy trinity behind terroir. Yet, recent research and the revolution in microbial ecology are shifting this narrative. Could it be that tiny, invisible life forms—microbes—define terroir more than the soil itself?

Welcome to a world where microbes are the quiet artisans behind flavor, aroma, and the soul of a wine or craft beer. This article dives deep into the science, exploring how microbial communities interact with grapevines, barley, hops, and even the cellar environment to create products that taste undeniably of place.

Understanding Terroir: Beyond Soil and Sunlight

Terroir, a French term often translated as “sense of place,” encompasses environmental factors that influence agricultural products. Traditionally, soil has been considered the backbone of terroir. It provides:

- Mineral content: Essential nutrients like potassium, magnesium, and calcium influence vine health and grape composition.

- Texture and drainage: Clay, sand, and silt proportions affect root development and water availability.

- Microclimate interactions: Soil type can influence temperature retention, humidity, and frost risk.

Yet, despite soil’s importance, winemakers and scientists alike have noticed inconsistencies. Grapes from the same soil type in neighboring vineyards can produce wines that taste strikingly different. Similarly, the flavor profile of craft beers using the same barley and water can vary across breweries, even when production methods are identical. The missing variable? Microbes.

Microbes as Terroir Architects

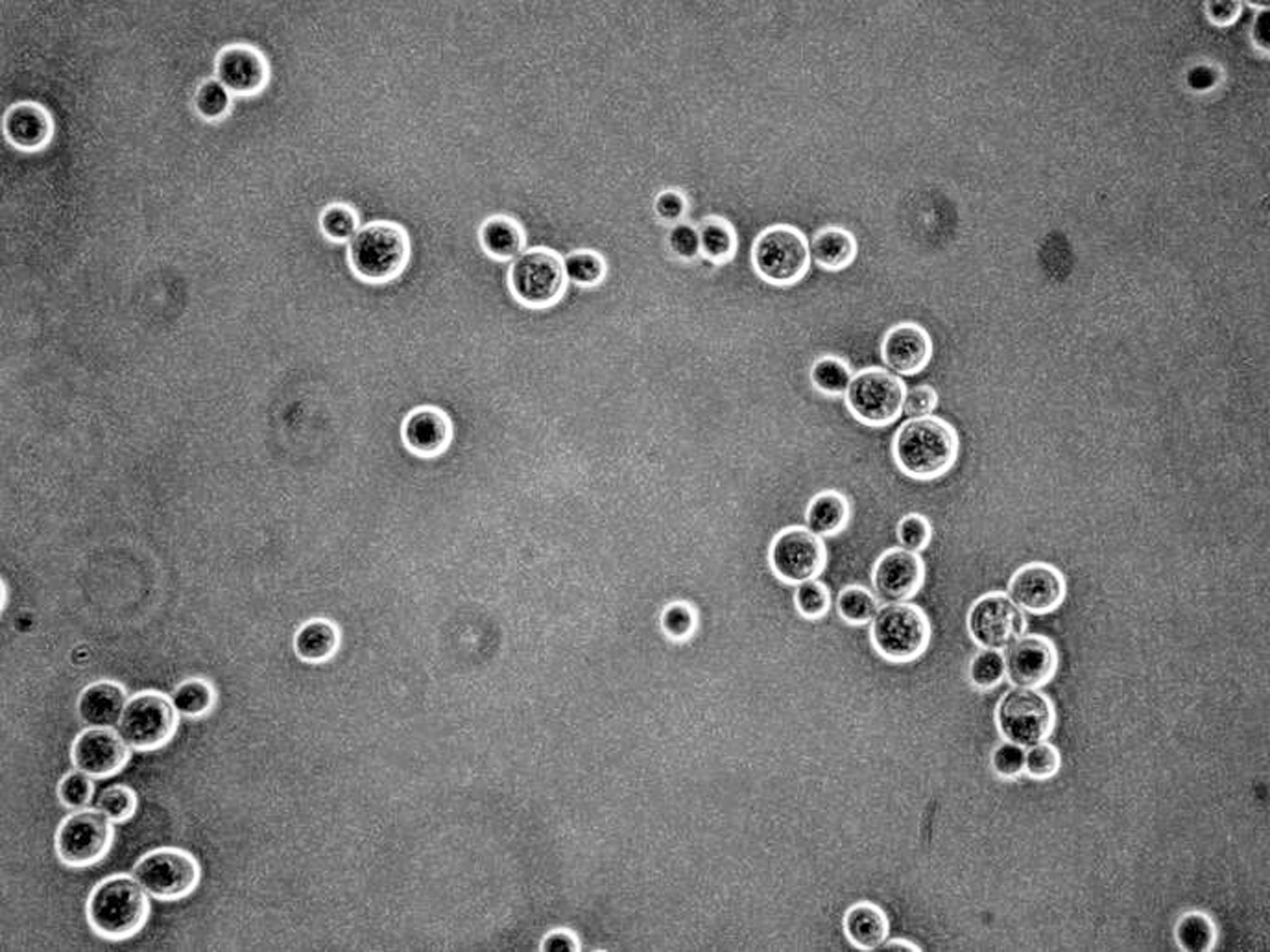

Microbes, the microscopic organisms inhabiting soil, grape skins, must, and fermenting vessels, are emerging as key influencers of terroir. The two major microbial groups in focus are:

- Bacteria: Including lactic acid bacteria, acetic acid bacteria, and other soil-dwelling species.

- Fungi: Yeasts (like Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and filamentous fungi (like Botrytis) that dominate fermentation and grapevine health.

These microbes influence flavor and aroma through several mechanisms:

- Fermentation: Yeasts convert sugars into alcohol and aromatic compounds. Different yeast strains produce varying levels of esters, higher alcohols, and phenolic compounds that define a wine’s bouquet.

- Metabolite production: Some bacteria generate lactic acid, acetic acid, or volatile phenols, subtly modifying taste and mouthfeel.

- Grapevine health modulation: Microbes can protect against pathogens, influence nutrient uptake, and affect grape chemistry indirectly, changing sugar-acid ratios that shape flavor profiles.

In short, microbes act as both chemists and guardians, modulating flavor at multiple stages of production.

The Vineyard Microbiome

Recent studies have shown that the vineyard microbiome, the community of microbes living on leaves, roots, and grapes, can vary from block to block, even when soil appears identical. This variability can be influenced by:

- Climate: Temperature, rainfall, and humidity affect microbial growth and diversity.

- Agricultural practices: Organic farming, pesticide use, and tilling can alter microbial populations.

- Grape variety: Different cultivars host distinct microbial communities.

One compelling finding is that grape-associated microbes are often more predictive of wine style than soil composition. This is because grape microbes influence the initial stages of fermentation, setting the stage for dominant flavor compounds.

Microbes in Fermentation: The Flavor Magicians

Fermentation is where microbes truly shine. Without microbes, wine, beer, and spirits would remain sugary liquids. With microbes, they transform into aromatic, flavorful products.

- Yeast and Aromatics

Yeasts are responsible for the primary fermentation, but not all yeasts are equal. Wild yeasts present on grape skins differ from commercial strains. Wild fermentation can produce nuanced esters and phenols, leading to flavor notes described as floral, fruity, earthy, or even “barnyardy”—a complexity that commercial yeasts often cannot replicate. - Bacteria and Complexity

Malolactic bacteria (like Oenococcus oeni) convert sharp malic acid into softer lactic acid, smoothing wine texture and subtly influencing aroma. Similarly, certain acetic acid bacteria can impart vinegar-like notes if uncontrolled but contribute positive complexity in minute amounts. - Microbial Succession

During fermentation, microbial communities shift. Early colonizers consume sugars rapidly, altering the environment to favor other microbes that produce unique flavor compounds. This dynamic process creates a fingerprint of the vineyard’s microbial terroir, captured in the final product.

Comparing Soil vs. Microbe Influence

At this point, it’s tempting to ask: does soil matter at all? The answer is yes—but perhaps less than previously thought. Soil primarily:

- Provides nutrients and water to the vine.

- Shapes vine vigor and grape composition.

- Influences stress responses that indirectly affect grape metabolites.

However, the microbial signature on grapes can be far more predictive of wine aroma and flavor than soil chemistry. In other words, soil sets the stage, but microbes write the script.

Some experimental evidence illustrates this beautifully:

- Researchers transplanted grapevines from one region to another while keeping soil constant. The wines retained flavor characteristics of the origin region, linked to persistent microbial communities.

- In brewing, breweries using identical barley, water, and hops produced distinctly different beers because local yeast and bacteria contributed unique metabolic fingerprints.

In essence, microbes act as taste architects, capable of imprinting regional identity on agricultural products, independent of soil.

Beyond Wine: Microbial Terroir in Beer and Spirits

The concept of microbial terroir extends far beyond vineyards. In craft beer, sour beers and spontaneously fermented brews showcase microbes as terroir-defining agents. Consider Lambic beers from Belgium:

- Fermentation relies entirely on wild microbes from the brewery environment.

- The same ingredients in a different region produce dramatically different flavors due to microbial variability.

Similarly, in whiskey, rum, and other spirits:

- Fermentation microbes affect congeners, acids, and esters that survive distillation.

- Even post-distillation, barrel microbes can contribute subtle aromatic complexity during aging.

This microbial influence suggests terroir is not limited to soil or geography but is a living ecosystem encompassing the microbes interacting with raw materials.

The Science of Mapping Microbial Terroir

Advances in DNA sequencing and metagenomics have revolutionized our ability to map microbial communities. Scientists can now:

- Identify the exact species present on grape skins or in brewing vessels.

- Track microbial succession during fermentation.

- Correlate microbial presence with flavor compounds in the final product.

These techniques reveal patterns that were previously invisible, showing that microbial diversity often aligns with regional flavor signatures. For instance, a vineyard with high yeast diversity may produce wines with complex aromatic profiles, while one dominated by a single species might result in simpler wines.

How Microbes Interact with Soil and Climate

While microbes can define terroir, they are not entirely independent of soil or climate:

- Soil chemistry influences which microbes thrive. For example, acidic soils favor certain lactic acid bacteria.

- Climate affects microbial growth rates and population dynamics.

- Farming practices can enhance or suppress microbial diversity.

Thus, terroir emerges from a synergy between soil, climate, and microbial ecology, but microbes may be the decisive factor shaping taste and aroma.

Microbial Preservation of Traditional Terroir

An unexpected benefit of understanding microbial terroir is the potential to preserve traditional flavors. As climate change, industrialization, and monoculture farming threaten regional identity, conserving native microbial populations becomes critical:

- Vineyards can nurture natural yeast and bacteria rather than relying solely on commercial strains.

- Breweries can inoculate batches with region-specific microbes to maintain traditional flavors.

- Barrel management can encourage beneficial microbes, enhancing aging complexity.

In short, microbial stewardship is emerging as a tool for cultural and gastronomic preservation.

Challenges in Embracing Microbial Terroir

Despite its promise, microbial terroir is not without challenges:

- Variability: Microbes are highly sensitive to environmental fluctuations.

- Predictability: Unlike soil nutrients, microbial activity is dynamic, making flavor outcomes less controllable.

- Pathogen risk: Some microbes can spoil products or pose health risks if not managed carefully.

Yet, modern technology—metagenomic mapping, fermentation monitoring, and controlled inoculation—can help producers harness microbial diversity while minimizing risk.

Microbial Terroir in a Changing World

As climate patterns shift, traditional soil-based terroir models may struggle to explain flavor variations. Microbes, however, are highly adaptable, capable of evolving alongside crops and fermentation processes. Understanding microbial terroir may help:

- Maintain flavor consistency despite climate stress.

- Identify novel flavor profiles unique to changing environments.

- Guide sustainable farming practices that support microbial diversity.

In essence, microbes may be nature’s flavor insurance, preserving regional identity in the face of uncertainty.

Practical Implications for Winemakers, Brewers, and Distillers

Producers can leverage microbial terroir in several ways:

- Microbial mapping: Cataloging the vineyard or brewery microbiome to predict flavor outcomes.

- Selective inoculation: Using native strains to guide fermentation while maintaining authenticity.

- Environmental stewardship: Minimizing chemical interventions that reduce microbial diversity.

- Cross-region comparisons: Understanding how microbial communities differ even between adjacent sites, informing blending strategies.

By focusing on microbes, producers can enhance complexity, deepen regional identity, and create products that truly taste of their place of origin.

Conclusion: The Microbial Revolution of Terroir

Terroir has long been romanticized as soil, climate, and human touch. Yet, the invisible world of microbes is proving to be a powerful architect of taste. From vineyards to breweries, from fermentation tanks to aging barrels, microbial communities shape aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel in ways that soil alone cannot explain.

So, can microbes define terroir more than soil? Evidence increasingly suggests yes. While soil sets the stage, microbes compose the music, coloring each sip with the subtle fingerprint of a place and time. Embracing this microbial perspective is not only a scientific advance but also a journey into the living essence of flavor—dynamic, complex, and astonishingly local.

The next time you swirl a glass of wine, sip a sour beer, or savor a barrel-aged whiskey, remember: the story you taste is not only that of the land but of the countless microscopic artisans that live there, silently shaping the flavor of place.