For wine lovers, the mere mention of “cork taint” can provoke a shiver akin to discovering a fly in your soup. It’s that invisible villain lurking in bottles, capable of turning an anticipated symphony of flavors into a muted, musty mess. Traditionally, cork taint has been treated as a rare, almost mythical phenomenon—something that afflicts only a small percentage of wines. But the question deserves a closer, more nuanced inspection: is cork taint truly as rare as we think, or has the wine world been lulled into a comforting, misleading assumption?

What is Cork Taint?

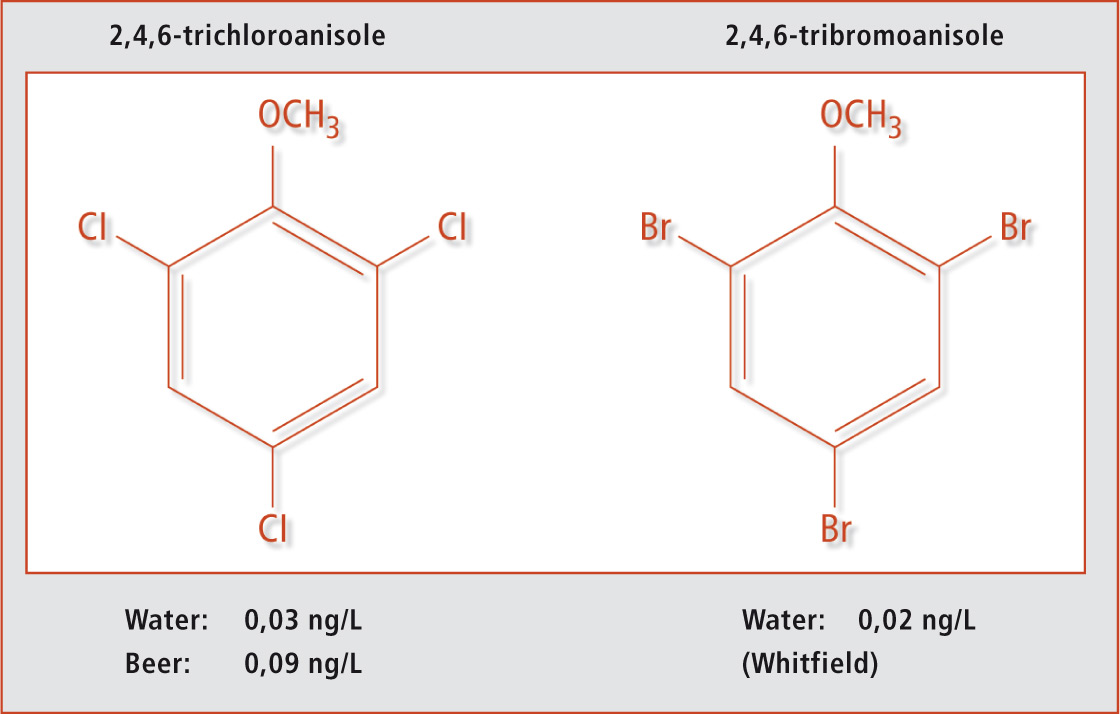

Cork taint is primarily caused by a compound called 2,4,6-trichloroanisole, commonly abbreviated as TCA. TCA forms when natural fungi present in cork react with chlorinated phenols, often introduced during cork processing or from environmental contamination. The result is a wine that smells off, often described as musty, damp cardboard, or moldy basement. In taste, it dulls the wine, masking its fruit, aromatics, and complexity. A wine with cork taint can lose its vibrancy entirely, sometimes in subtle ways, sometimes dramatically.

The problem lies in the invisibility and subtlety of the defect. Unlike a broken bottle or a sour wine, cork taint doesn’t scream for attention. Some aficionados can detect it immediately, while casual drinkers may only sense a vague “offness” in the wine, sometimes attributing it to personal taste rather than a flaw in the bottle.

How Common Is Cork Taint?

Historically, wine producers and enthusiasts have estimated cork taint prevalence at around 1-5% of bottled wines, depending on the source. Early studies and industry claims leaned toward the lower end, suggesting that cork taint was an uncommon, almost anecdotal concern.

However, recent investigations have suggested that cork taint might be more frequent than widely acknowledged. Blind tasting experiments, surveys of consumers returning bottles for replacement, and laboratory testing indicate that TCA contamination could affect up to 10% of wines sealed with natural corks. That number jumps when factoring in wines where the defect is subtle enough that it goes unnoticed at first sip.

So why the discrepancy? Part of the answer lies in detection. TCA is incredibly potent—even a few nanograms per liter can be detected by the human nose. Yet the perception of cork taint is subjective. Different people have varying sensitivity to TCA, which means a wine deemed “tainted” by one taster might be acceptable to another. Furthermore, the cultural narrative surrounding cork—the romance of tradition, the tactile pleasure of pulling a cork—may bias consumers and producers alike to downplay minor defects.

The Science Behind TCA Formation

Understanding cork taint requires a dive into chemistry. TCA is not present in cork naturally; rather, it arises through a complex interplay of fungi and chlorinated compounds. Chlorophenols can enter the cork through several channels:

- Agricultural treatments – Fungicides and pesticides containing chlorinated compounds were historically used in cork oak plantations.

- Bleaching and processing – Some corks undergo chlorine-based bleaching to achieve uniformity in color, which can react with cork fungi to form TCA.

- Environmental contamination – Chemicals from nearby industrial processes or even contaminated water used during cork washing can contribute to TCA formation.

Once TCA is present, it can migrate into the wine, even at extremely low concentrations. Sensory studies show that humans can detect TCA at levels as low as 1–5 parts per trillion—equivalent to a drop of ink in an Olympic swimming pool. This makes even a minuscule amount enough to spoil an entire bottle.

Interestingly, TCA is not the only compound responsible for cork-related flaws. Other chloroanisoles, such as TeCA and PCA, can produce similar sensory effects. However, TCA remains the most notorious and frequently studied.

Cork Taint vs. Other Wine Faults

To put cork taint in context, it helps to compare it to other common wine flaws. Acetic acid, for instance, produces volatile acidity—a sharp vinegar-like scent—but is usually easier to identify. Brettanomyces yeast, known as “Brett,” can introduce barnyard or medicinal aromas, which some enthusiasts even find desirable in small doses. Oxidation, microbial spoilage, and sulfur compounds each have their own signatures, but cork taint is unique because of its subtlety, consistency, and ability to remain undetected until the cork is removed.

This subtlety has contributed to the myth of rarity. Unlike a spoiled milk-like fault, cork taint doesn’t always elicit an immediate reaction. Many casual drinkers may never realize they’ve encountered it, while connoisseurs may encounter it more often simply due to repeated exposure.

Natural Cork: A Double-Edged Sword

The traditional crown jewel of wine sealing, natural cork, is both revered and blamed. It’s harvested sustainably from cork oak bark and has remarkable elasticity, creating a near-perfect seal while allowing microscopic oxygen exchange, which can benefit wine aging. But cork’s very nature as a biological material makes it susceptible to TCA formation.

Producers have long attempted to minimize risk. Washing corks, steam sterilization, and sophisticated quality controls have dramatically reduced the occurrence of tainted corks in recent decades. One notable technique, the “cork washing and sorting” process, removes contaminated corks before they reach bottling. Another innovation involves micro-agglomerated corks, which combine natural cork pieces with adhesives and minimize TCA contamination while retaining some natural properties.

Despite these advances, natural cork will never be completely immune to TCA because it’s inherently organic. The key lies in prevention, early detection, and consumer awareness.

Alternatives to Natural Cork

Given the specter of cork taint, winemakers have explored numerous alternatives:

- Synthetic corks – Made of plastic or polymer blends, synthetic corks eliminate TCA risk entirely. However, they may introduce other challenges, such as inconsistent oxygen permeability or negative sensory interactions with wine over time.

- Screw caps – Once considered taboo among fine wine producers, screw caps have gained widespread acceptance. They create an airtight seal, virtually eliminating cork taint and reducing oxidation risk. Critics argue that screw caps can produce reductive aromas (like sulfur or eggy smells) if the wine is not properly managed, but modern technology has minimized these issues.

- Glass stoppers – Elegant and inert, glass stoppers remove biological risk entirely while maintaining some aesthetic appeal. They are more expensive and less flexible than cork, limiting widespread adoption.

Each alternative has trade-offs. While they reduce TCA risk, some wine enthusiasts feel they lack the tactile and ceremonial qualities of natural cork. This tension between tradition and technology has fueled debates in the wine industry for decades.

Detecting Cork Taint

For consumers, detecting cork taint can be tricky. The first hint is usually olfactory: that musty, damp, cardboard-like aroma. Tasting is the next confirmation. Wines affected by TCA often lose fruitiness, vibrancy, and complexity, leaving behind a dull, flat, and sometimes slightly bitter profile.

Professional sensory panels and laboratory analysis can identify TCA at extremely low concentrations. Techniques such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) provide precise measurements, confirming contamination even when it’s imperceptible to casual tasters.

Interestingly, some studies suggest that exposure to cork taint may be cumulative in perception. Regular wine drinkers might become desensitized to TCA over time, or conversely, develop hyper-sensitivity after repeated experiences. This further complicates claims about how rare cork taint truly is, as personal perception plays a huge role in reporting.

How the Industry Handles Cork Taint

The wine industry has developed protocols to minimize TCA risk and respond when it occurs. Reputable producers often replace tainted bottles without question, and distributors may test cork batches for TCA before bottling. Quality assurance now includes sensory testing, chemical analysis, and supplier audits, creating a multilayered defense against cork taint.

Despite these precautions, some experts believe cork taint is underreported. Small producers may lack access to sophisticated testing, and consumers may return bottles infrequently or fail to report subtle defects. Consequently, the real-world prevalence of cork taint could exceed industry estimates, lending credibility to the idea that it is not as rare as we like to think.

The Consumer Perspective

For wine enthusiasts, cork taint is more than a chemical problem—it’s an emotional one. Opening a highly anticipated bottle and detecting the musty stench can be profoundly disappointing, disrupting the sensory and cultural ritual of wine drinking.

Yet awareness is increasing. Sommeliers, wine educators, and journalists now openly discuss cork taint, helping consumers recognize it and seek replacements when necessary. Some aficionados even consider cork taint a form of educational seasoning, sharpening their sensory perception and deepening appreciation for wine quality and provenance.

Is Cork Taint a Threat to the Wine Market?

While cork taint has a dramatic personal impact, its threat to the overall wine market is limited. Advances in cork processing, alternative closures, and quality control have reduced major incidents. Modern consumers have also adapted—screw caps are now widely accepted, particularly for wines intended for early drinking.

Interestingly, cork taint may even have an unexpected marketing upside. Wine producers emphasize traditional cork sealing as a symbol of quality and heritage. The rarity of cork taint is part of this narrative; by framing it as uncommon, producers reinforce the allure of natural cork while acknowledging that minor risk is part of the wine experience.

Myths and Misconceptions

Several myths surround cork taint:

- All natural corks are contaminated – False. Only a small percentage are affected, and modern production methods minimize risk.

- Synthetic corks or screw caps ruin wine – Partially false. While they alter oxygen interaction, they do not inherently damage wine quality.

- Cork taint can be “cooked out” – False. TCA contamination cannot be eliminated once it has entered the wine.

- Cork taint only affects expensive wines – False. Any bottle sealed with natural cork can be affected, from inexpensive everyday bottles to premium vintages.

Understanding these myths helps consumers approach cork taint with knowledge rather than fear.

Cultural and Historical Context

Cork taint has shaped wine culture for centuries. In earlier eras, when cork processing was less sophisticated, tainted bottles were likely more common. The modern obsession with perfect wine has amplified awareness of cork flaws. Interestingly, TCA detection has influenced viticulture, winemaking practices, and even marketing strategies.

Cork taint also interacts with wine terroir and provenance. Regions with strict cork quality control—Portugal’s cork-producing regions, for instance—tend to produce bottles with lower taint incidence. High-end producers emphasize cork selection and testing as part of their narrative, linking material science with heritage storytelling.

Practical Advice for Wine Lovers

For those who wish to minimize the chance of encountering cork taint:

- Look for trusted producers – Brands with rigorous quality control report lower taint rates.

- Consider alternative closures – Screw caps and synthetic corks can eliminate TCA risk entirely.

- Trust your senses – Smell and taste your wine critically. If something seems off, it probably is.

- Don’t overemphasize rarity – Cork taint is more common than many claim, but its occurrence is manageable and predictable.

Conclusion: Rarity or Illusion?

So, is cork taint really as rare as we think? The short answer is: no, not exactly. While traditional estimates placed its prevalence at a low percentage, emerging evidence suggests that subtle contamination may affect more bottles than widely acknowledged. However, modern detection, processing, and alternative closures have made severe cases relatively uncommon.

Ultimately, cork taint is both a scientific and cultural phenomenon. It reminds us of the delicate interplay between human craftsmanship and natural imperfection. Even as technology reduces risk, cork taint retains a mystique, a symbol of wine’s organic complexity. For lovers of the craft, understanding and recognizing it is part of the journey—a tiny imperfection that makes the pursuit of perfect wine all the more rewarding.